DNS

March 2024

The core idea of DNS is simple to understand. You give a domain name and get back the IP of it. Though, there is A LOT that goes on behind the scenes in making that happen for you. And it happens really fast. Today, I'd like to take you down this rabbit hole and by the end of it, I hope to give you a great amount of clarity on what goes on.

If we were tasked with designing a system like this, most of us would begin with a single database. We would store all the domain names and their IP addresses in a table-like structure, maybe put an index on it and call it a day, right?

But here's the problem. Quick google searches reveal that there are over 600 million+ domains in the world. And there are billions of DNS queries happening every day. That's an insane amount of scale. Is a single big table really capable of handling that? Not really.

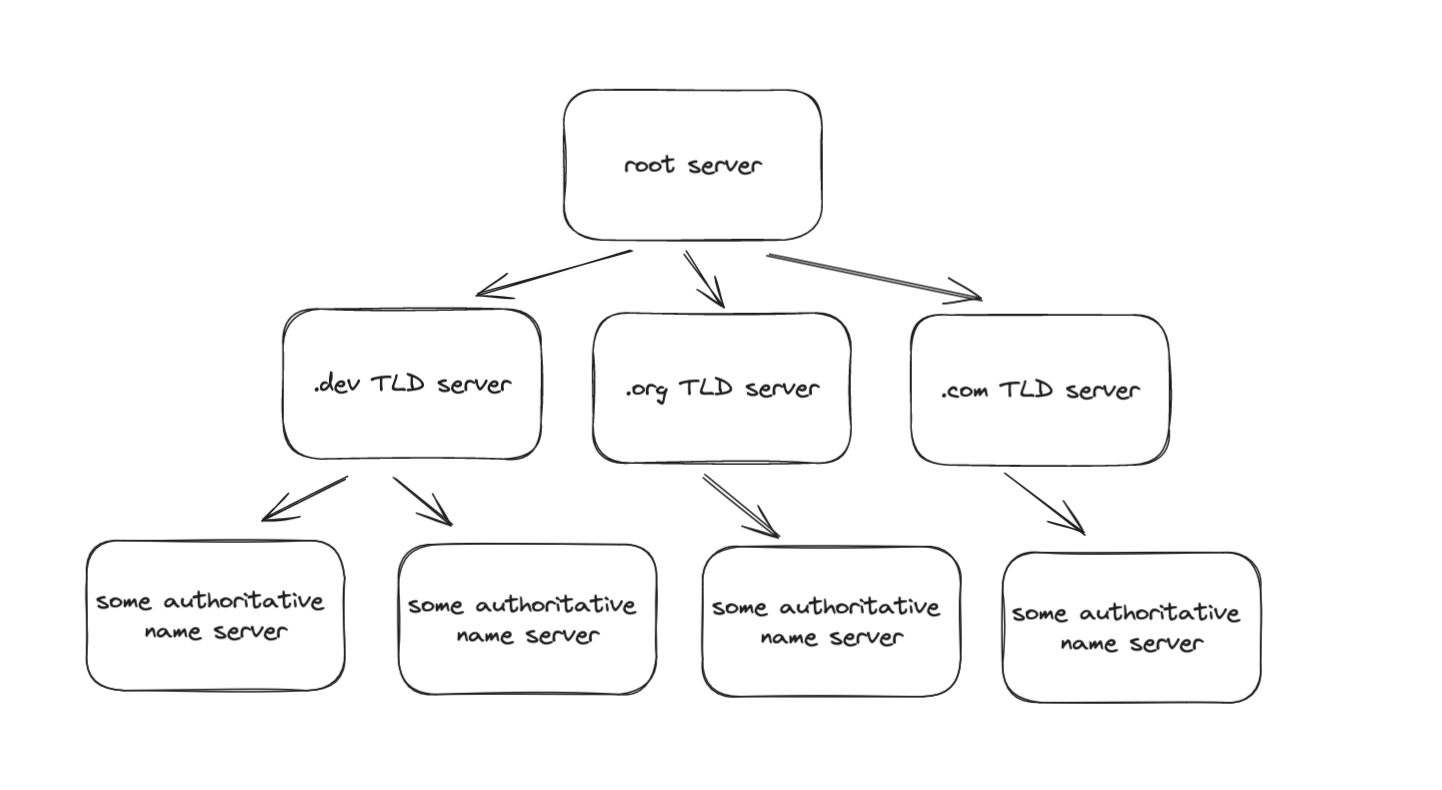

So, maybe you could shard? Hmm, that makes sense. But on what basis will you split the table? You could perhaps shard on the basis of geography of the registered domain. That could work. But here's the thing. In our design, sharding is an after thought. What if we could have a system that is fundamentally sharded across the world. This is the neat idea behind DNS. It has a tree-like structure in the world. Let's understand this tree.

the tree

The root servers sit at the top most layer. For a given query, they will either return the IP if they have it or most likely, they will tell the address of another server that you can hit. This second server in the hierarchy is the TLD (top level domain) server. TLD is the last segment of a domain name, located after the last dot, such as .com, .org, .net, .gov, .edu, etc.

If you ask the root server for the IP of google.com, it will find the TLD of google.com, which is ".com". From the ".com" server, you will be able to find the information for all the domains that lie in the ".com" space.

Just because there are 13 fixed IPs in the world for root servers, it does not mean that there are only 13 actual servers handling this scale. With the help of Anycast routing, multiple servers are mapped to each of these 13 IP addresses and they all share the load amongst themselves. As per cloudflare, there are 600+ such servers in the world.

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) operates servers for one of the 13 IP addresses in the root zone and has delegated operations of the other 12 IP addresses to other organizations in the world.

If you are writing software that has to serve DNS queries, you need to start somewhere. So you are typically required to hardcode the IP address of these 13 servers. This is also how it is done everywhere. The good thing is that, this list almost never changes.

The TLD server now has a smaller set of data to deal with it. It is only concerned with the domain it belongs to. But interestingly, the breakup does not end here. A DNS query sent to a TLD server is further redirected to something called as the authoritative nameserver. The authoritative nameserver is usually your last step in the journey for finding an IP address. The authoritative nameserver contains information specific to the domain name it serves.

the zone file

DNS is managed in a hierarchy using something called as zones. It is a portion of the domain name space for which administrative responsibility has been delegated. All of the information for a zone is stored in what’s called a DNS zone file. A zone file's structure is outlined in RFC 1035 and RFC 1034. However, many modern-day DNS servers use this file as a starting point to compile the data into a database format and use their own storage mechanisms internally. Some of them (like Amazon's Route 53) allow you to even export the data into a zone file format.

the resolver

Now you know that you have to start with a root server and work your way down the tree till you find your IP. The software that does this for you is called as the resolver. There are many DNS resolvers out here in the world. Google has its own. Cloudflare has its own. When you connect to the internet, your ISP also assigns a resolver for your device. You have the option to override this and choose any other resolver in the world as your own. Heck, you can even write one on your own. As a learning exercise, I wrote one. But I wouldn't recommend using it as your default resolver for your network unless you have battle tested it.

I would like to highlight some interesting things I learnt while implementing this resolver.

- The DNS RFC is a gold mine for understanding the actual flow of data in a DNS query. Being a spec for implementers, it does not shy away from detailing the actual structures involved.

- One component in a domain name (separated by a dot) can only be 63 characters long. For a domain name, a.b.c, the max size of a, b, and c, is 63 characters each. This has interesting implications, elaborated next.

- In a packet sent across the network by a name server, the domain name is actually compressed! Let's say we have a DNS message that needs to include the domain name "example.com" multiple times. Without compression, each occurrence of "example.com" would need to be fully written out in the message. However, with DNS compression, subsequent occurrences can be replaced with a pointer to the first occurrence. In the length field that describes how long the name is, every time we get the two starting bits as 1s, we know that the message that follows is actually a compressed one. Since domain components are only 63 characters long, you cannot have your starting bits as 1s, indicating this is definitely compressed. This is pretty neat.

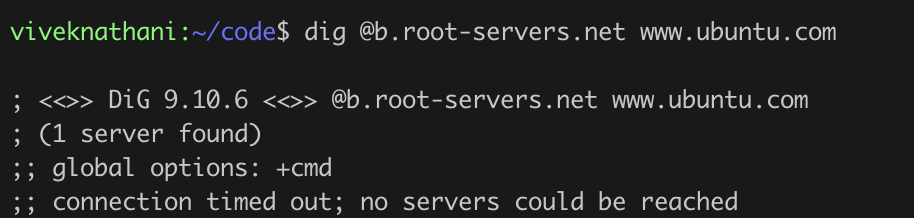

- ISPs apparently block direct access to root servers. While taking my program for a test drive, I sent a query to one of the 13 IP addresses, and it timed out. I tried to do it via the

digutility, and it failed there too. Switched to a different ISP, and it worked! Tried on my Linode VM and it worked there too. This means you are at the mercy of your ISP if you wish to run your own resolver. That sucks imo.

shit blowing up in production

DNS is a critical component of the internet infrastructure. But there are pretty interesting incidents in history where it has contributed to some global outages.

In July 2021, the Akamai DNS service was down. This disruption led to major websites like PlayStation Network, Fidelity, FedEx, Steam, AT&T, Amazon, and AWS becoming inaccessible.

In April 2021, Azure DNS servers experienced a surge in DNS queries. The service became overloaded. And this lasted for more than an hour. Clients were not able to access Microsoft and Azure services. Pretty wild imo.

what happens when you update your DNS?

This is a pretty interesting topic. A lot of us have done it atleast once in our lives. But I think Julia Evans does a great job at explaining what happens here. So I will just link her blog post here.

closing thoughts

After having some first-hand experience with services going out of hand at work and seeing it happen elsewhere, I truly get why reliability and availability are pretty important guarantees for systems on the internet. DNS is an interesting example of a system that is extremely well designed and can yet be the root cause of many outages.

Also, I love all the work that Cloudflare has done in trying to make the internet more reliable. They keep releasing interesting projects that revolve around computer networking and infrastructure. I am in awe of everything they do.

Vivek.

<- back to home