grokking NAT and packet mangling in linux

Source: Imgur

Imagine a house full of devices connected to your Wi-Fi network. From any device, try finding your public IP by visiting https://www.whatismyip.com/. The IPv4 address field should be the same for all devices. This is the IP provided by your Internet Service Provider (ISP) to your router, which acts as a gateway for your internet.

So what's happening here? If the IPv4 address is the same, how is the router able to differentiate between the devices? Why can't we just assign a unique IPv4 address to each device?

Well, the size of an IPv4 address is 4 bytes or 32 bits. Therefore, there can be 2^32 unique IPv4 addresses in the world. 2^32 = 4,294,967,296. ~4 billion addresses. Now, imagine a data center trying to set up a network of thousands of servers. Imagine a household with 5 devices. Imagine a corporation with thousands of employees, each having at least 1 device. If we were to assign a unique IPv4 address to each device, we'd run out of addresses pretty quickly.

Networking class 101 may tell you about IPv6 as well. And if you do the math (2^128), IPv6 can support up to 340 undecillion addresses. That's a lot of addresses! So this should fix the IPv4 problem, right? Just migrate to IPv6 and call it a day! Except - the reality is disappointing. For this to happen, every single ISP in the world needs to move to IPv6. Every piece of hardware and software in the world that was written with IPv4 in mind needs to accept IPv6. Transitioning requires running IPv4 and IPv6 side-by-side for a while. Applications need to be updated to support IPv6. Bottom line: It's a lot of work.

So what do we do until then? Well, what if every routing device had a unique, publicly visible IPv4 address and every device inside that network had a private IPv4 address? And what if the router was to maintain a table mapping like:

${private_ip}:${private_port} -> ${shared_public_ip}:${public_port}`

The router would just have to rewrite the packet headers before forwarding them.

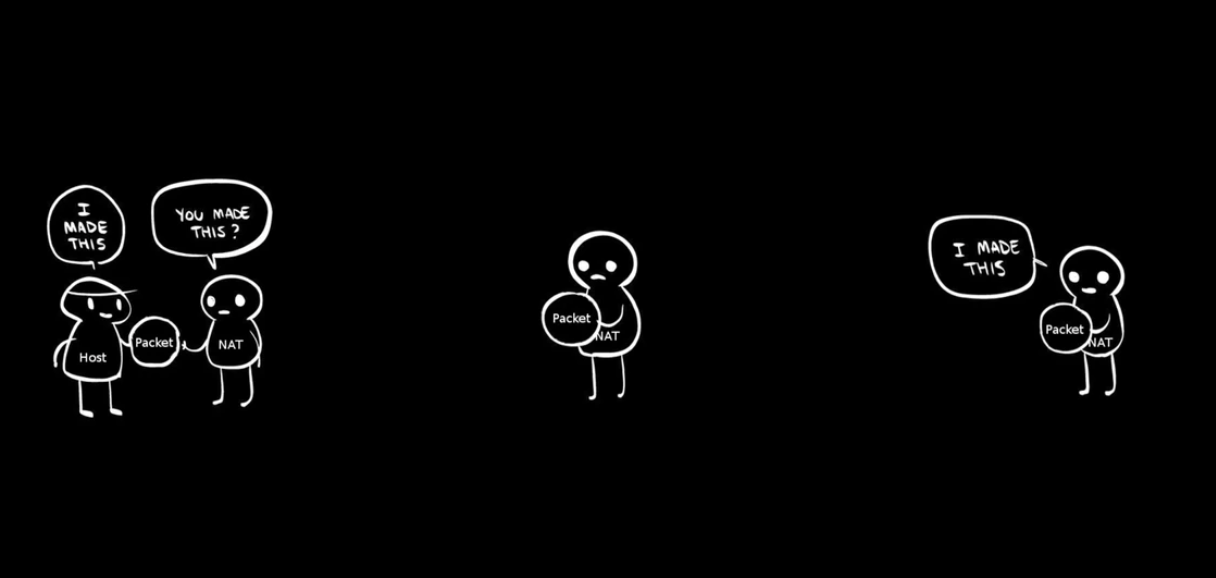

That is the idea behind Network Address Translation (NAT).

history

As per the RFC 1631 from 1994, NAT was proposed as a short-term solution to the IPv4 address shortage problem. Today, in 2025, NAT is widely used everywhere.

A patch work that stayed forever. Seems familiar?

Overhead cables that were supposed to be underground. Source: Twitter.

types

- Basic / Static NAT

The simplest type of NAT provides a one-to-one translation of IP addresses. Let's take examples of two networks that use different IP ranges:

Network A: uses 192.168.1.0/24

Network B: uses 10.0.0.0/24

If you need a device on Network A to communicate with Network B, you can use a NAT device to translate the IP addresses.

An example mapping would look like this:

192.168.1.10 (Network A) <-> 10.0.0.10 (Network B equivalent)

- Port Address Translation (PAT)

Basic NAT is too simplistic to support multiple devices on the same network. Port Address Translation (PAT) is a technique that allows multiple devices on a private network to share a single public IP address by using different ports. Instead of using just a single private IP to public IP mapping, PAT uses a combination of IP and port numbers to uniquely identify each device.

- Full Cone NAT / One-to-One NAT / NAT 1

Once an internal device sends a packet to an external host, any external host can send a packet to this internal device, provided it knows the public IP and port.

- Restricted Cone NAT / NAT 2

Similar to full cone NAT, but with an added restriction. Only external hosts that you have previously sent packets to can send packets back to you.

- Port Restricted Cone NAT / NAT 3

A stricter version of restricted cone NAT. Not only must an external host match the IP address, but it must also match the port number as specified in the outbound communication.

- Symmetric NAT / NAT 4

This is the most restrictive type of NAT. All requests sent from the same private IP address and port to a specific destination IP address and port are mapped to the same IP address and port. If a host sends a packet with the same source IP address and port number to a different destination, a different NAT mapping is used.

For people who are building applications that rely on WebRTC, this type of NAT makes WebRTC impossible to work via STUN. You need to use a TURN server to relay packets between the two devices.

You can check what type of NAT you have by using a tool like Check My NAT.

It is important to note that the types in the list above are not mutually exclusive. A PAT like behaviour is seen in conjunction with Restricted Cone NAT, for instance.

so how do routers implement NAT?

Router operating system projects like OpenWrt use linux under the hood, specifically the nftables module. I went in and took a look at the nftables source code in linux.

Since NAT is about manipulating IP addresses and ports, it only makes sense to talk about it when TCP and UDP are involved. This is in alignment with what we see in nfnathelper.h. There are two core functions in this header: nf_nat_mangle_udp_packet and nf_nat_mangle_tcp_packet.

Let's take a look at nf_nat_mangle_udp_packet.

if (skb_ensure_writable(skb, skb->len)) return false;

Before NAT can edit anything, it makes sure the packet memory is writable. I like the assume-nothing approach. Neat explicit check for mutability.

if (rep_len > match_len &&

rep_len - match_len > skb_tailroom(skb) &&

!enlarge_skb(skb, rep_len - match_len))

return false;

If the replacement string is longer than the original, and there's not enough space, try to expand the buffer. If that fails, bail.

mangle_contents(skb, protoff + sizeof(*udph),

match_offset, match_len, rep_buffer, rep_len);

This is the core: replace match_len bytes at match_offset with rep_len bytes from rep_buffer. It modifies actual payload contents inside the packets on the wire.

udph->len = htons(datalen);

When you change the payload size, you must update the header's .len field to match the new packet length.

nf_nat_csum_recalc(...)

NAT is not just about IPs and ports. It must update checksums so the packet remains valid. Otherwise, the receiving host will reject it as corrupted.

So NAT is kind of a packet surgery, done live in the data path!

NAT around you as an engineer - docker!

Even if you’ve never written a firewall rule in your life, if you’ve used docker, you’ve been relying on linux NAT. Every time you run:

docker run -p 8080:80 nginx # ${host_port}:${container_port}

As per docker's docs, they use iptables. So we should expect a rule like this:

iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -p tcp --dport 8080 -j DNAT --to-destination 172.17.0.2:80

This tells the linux kernel: “If a packet comes to port 8080 on the host, rewrite its destination IP and port to send it into the container.”

The point is: NAT isn't just a data-center or an ISP thing. It's everywhere!

limitations

While NAT (Network Address Translation) has helped the internet scale beyond IPv4 limits, it’s not a perfect solution.

Issues:

- It breaks end-to-end connectivity.

- It makes encryption harder because it changes the packet headers.

- It complicates peer-to-peer apps. Added complexity and sometimes even added latency.

- Requires memory to exist since it has to maintain a mapping of all connections.

IPv6

IPv6 can truly address the limitations of NAT. It provides a much larger address space, allowing for more devices to connect to the internet without the need for NAT.

As per https://www.google.com/intl/en/ipv6/statistics.html, we are not there yet.

Need help with your networking setup? Hire me! work@vivekn.dev

<- back to home